VISUALISING REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE

Côte d’Ivoire

A visual storytelling mentoring programme by the NOOR Foundation featuring works by:

Jean-David Niangoran, Emilia Doliani, Mira Mariani, Romane Dakwa, Zahui Yvann, Olivier Kouhadiani, Kra Kouassi

Mentored by:

Bénédicte Kurzen, Aïda Muluneh

Supported by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire

With around 1.500 billion tonnes of carbon found in the organic matter in soil worldwide, soils are the second largest store of carbon after the oceans (40.000 billion tonnes). There is more carbon in the soil than in the atmosphere and vegetation combined.

However, modern agricultural practices impoverish the soil and its capacity to act as a carbon sink. Deep tilling, fertilisers and pesticides disrupt the life cycle of the top soil’s layer, releasing massive quantities of CO2. The transformation of soil into dust causes desertification and reduces food productivity.

Regenerative agricultural practices such as no-till, cover crops between harvests and integrating livestock in the production can restore the soil’s capacity to sequester carbon from the atmosphere, reduce desertification and increase productivity. If these practices were to be adopted at a global scale, they could reverse climate change, provide farmers with stable incomes and produce highly nutritious food while restoring natural balance to the land.

But there is little consensus on what regenerative agriculture is and a large part of the agricultural sector is still resisting the transition. Access to knowledge is essential to foster societal change.

With the firm belief that visual storytelling can inspire change by sharing knowledge in accessible and compelling ways, the Embassy of The Kingdom of The Netherlands in Abidjan and the NOOR Foundation joined forces to support seven visual storytellers working in the region in the identification, research and realisation of stories that investigate and contextualise regenerative agriculture in Côte d’Ivoire.

Mentored for six months by photographers and visual storytellers Bénédicte Kurzen (France) and Aïda Muluneh (Ethiopia / based in Côte d’Ivoire), and free to choose their preferred means of visual language - including reportage, fine art photography and deep archival research, the participants explored their surroundings in search of subjects, stories, data and people who are implementing radical changes to the ways we farm for our food.

The adoption of regenerative agriculture practices has the potential to improve the livelihoods and resilience of farmers, processors and consumers. It can also help restore natural systems which, in the case of West Africa, are highly eroded from centuries of intensive farming.

Wásē

By Jean-David Niangoran

Dive into a world where the earth beneath our feet tells a fascinating story. My project, entitled “Wásē“, explores the crucial importance of soil in our lives and in the health of our planet.

Soil, that silent guardian of biodiversity, is the canvas on which life flourishes.

Without soil, there would be no agriculture, no life. This is where our planet’s greatest treasure trove of biodiversity resides, the very driving force behind our development. Soil nourishes not only our crops, but also a whole range of animal and plant life that shapes our world.

Yet despite its vital importance, our soil is in danger. The FAO is warning us that a third of the world’s agricultural land is in a state of deterioration, threatened by erosion, loss of biodiversity and pollution. In my photographic exploration, I delve into this complex relationship between man and the land, highlighting both its beauty and its fragility.

To bring this project to life, I immersed myself in an in-depth study of the soil, seeking to understand its very essence. I discovered a living, breathing universe, an entity that regenerates itself if we treat it with respect.

But the future of the soil is uncertain.

The growing pressure of agricultural production, the massive use of pesticides and rampant urbanisation are threatening its health and ours at the same time.

My project is a cry of alarm, an invitation to rethink our relationship with the earth that sustains us.

From my first encounters, it was clear that the experiences of the young people I met, appeared to me, to be important testimonies for the whole of humanity. Their talk of hope, desolation, tolerance, the future, and of peace and learning was for some, wise beyond their years, It also offered up a unique perspective on African youth and the role it is playing in the continent's development at this crucial point in its history.

This project aims to combat the prejudices and stereotypes often associated with African youth, the continent and its cultures. It shows the need to stay connected to one's origins while opening up to others.

JEAN-DAVID NIANGORAN

Instagram: @blvckvrtist

Jean-David Niangoran, aka Blvckvrtist, originally from Ivory Coast, is a photographer and visual storyteller whose works reflect the diversity of contemporary African society. Passionate self-taught, his bold visual language explores societal issues. His evocative image series such as 'FCFA' have attracted international attention. Honored with the SGBCI Young Talent Prize in 2021, he was then rewarded at the PARM Art Challenge in 2022. His work has been exhibited in Lagos, Nigeria, and Abidjan. In 2023, he joined the NOOR Foundation workshop in Abidjan, expanding his artistic horizon. It now adopts a conceptual and multidisciplinary approach, while retaining its artistic authenticity. Jean-David aspires to explore new cultural horizons and to question our relationship with the world. His audacity and commitment make him an essential figure in global contemporary art.

Xocolātl

By Emilia Doliani

“Chocolate” from the Nahuatl word “xocolātl”: “bitter water.”

This work comes from the South. Just like its author and cocoa itself, it has traveled between Latin America and West Africa, establishing a connection between two regions rarely associated.

Having grown up in a middle-class family in Argentina, I always perceived chocolate as a product reserved for special occasions, and in my childhood mind, its abundance symbolized a certain social status. My years in France then showed me a different situation, that of chocolate becoming a common thing, included in the weekly shopping list of many families. Two years in Côte d’Ivoire then introduced me to a new facet of this industry, its production, and then this photographic work led me to learn about its history, ultimately bringing me back to Latin America.

WestAfrica, the largest cocoaproducer, accounts for 70% ofglobal production.

Coordinates: 7°7’15.5353”S 76°45’45.209” W

WestAfrica, the largest cocoaproducer, accounts for 70% ofglobal production.

Coordinates: 5°56’58.9442” N 3°43’36.4128” W

The more I learned about cocoa, the more I realized that it embodied a striking example of the socio-economic and environmental challenges that we and our agricultural system are facing today. Requiring strict meteorological conditions and existing only in equatorial zones, it is particularly vulnerable to climate change, and the already observable impact crystallizes the risks we face today. Not only a victim, cocoa also proves to be responsible for climate change through the massive deforestation its production has caused. Nevertheless, it also opens perspectives on solutions, through, for example, agroforestry to which it is particularly suited. Through the blatant socio-economic imbalances of the industry that has developed around it, cocoa also questions us about the need to combine environmental preservation and economic justice. Finally, it is also its history that offers us a new perspective and questions us about the relevance of the system that has been put in place, this history of an initially unchosen link between two regions of the South that shared a climate and are now facing common challenges.

Sharing the lives of cocoa producers on both continents has been a unique experience, which I hope to visually convey through this day in the fields intertwining Côte d’Ivoire and Peru. From this experience, I come out convinced that efforts to make our agricultural system sustainable can only be relevant if they truly put producers at the center, who will be the main actors in implementing long-term solutions. I also hope that this project will inspire greater collaboration among Southern countries.

All the farmers who appear in this project implement regenerative agriculture practices.

The Huallaga River (a tributary of the Amazon) is an essential source of water and food, as well as a means of transport for the inhabitants of the San Martin region. Like the Mé in its namesake region in Côte d’Ivoire, it is an essential part of the local ecosystem.

Ramón Castilla village, San Martin department, Peru. After a morning’s work, Bertila prepares lunch for his family. In Latin America and West Africa, many farmers use improved stoves. These cookers are designed to be more efficient and environmentally friendly.

Chazuta, department of San Martin, Peru. Before starting his day’s work in his father’s field, Hilton (18) burns herbs to generate a protective smoke, particularly against mosquitoes. After the summer, he will continue his studies at the military academy.

David (33). Village of Madzazin, commune of Adzopé, Mé region, Côte d’Ivoire.

Cayena village, San Martin department, Peru. Marco (50) looking for a coconut to refresh himself after a day’s work. Agroforestry combines other trees with cocoa plants in the same plot. In particular, it provides protective shade for the cocoa, helps to preserve soil quality and diversifies farmers’ incomes. Combined with the protection of existing virgin forests, it can help combat climate change by absorbing carbon dioxide. The implementation of relevant agroforestry systems is still largely insufficient at sector level.

Village of Nyan, commune of Adzopé, Mé region, Côte d’Ivoire. Seph (35), returning home after a day’s work in the fields. Despite the efforts made, it is estimated that over 70% of farmers in West Africa do not earn a decent income from their work, enabling them to meet their basic needs. More than 30% live below the extreme poverty line

Juanjuí, department of San Martin, Peru. A passionate nature lover and owner of a 60-hectare plot of land, Americo (68) has decided to preserve the vast majority of his plot as primary forest, growing cocoa on just 3 hectares. Also a beekeeper and horticulturist, Americo hopes to develop ecotourism on his property based on what he himself calls his “oxygen route”, a hike he has mapped out in the heart of the primary forest that he and his wife Elida (64) have preserved.

EMILIA DOLIANI

Instagram: @emilia.doliani

Maria Emilia is a photographer from a small farming town in central Argentina.She graduated in 2017 with a Degree in Photography from the Superior School of Applied Arts in Cordoba. In 2018, she moved to Buenos Aires where she obtained a Licence in Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage at the National University of the Arts. The deterioration of the economic situation in Argentina convinced her to move to France, where she studied Art History and Archaeology at the Sorbonne University between 2020-2021. At the end of 2021, she moved to Abidjan in order to accompany her husband during his expatriation to Côte d’Ivoire. This decision has given a new perspective to her professional future, and has given me the opportunity to put my training in photography by working as a reporter-photographer for various companies, associations and foundations.

REGENERATION WOMEN

by Mira Mariani

I have followed the stories of women who act as guardians of their lands and communities around the cocoa planters.

Mafoudia is a passionate agronomy student who is writing a dissertation on the impact of climate change on the cocoa agroforestry system. She works on Ambroise N’kho’s plantation, an outstanding permaculture site. Mafoudia measures carbon emissions and soil health. After only 3 years of regenerative agriculture, biopesticides and composting, the soil is now healthy and rich in biodiversity.

She believes that the solution to the current cocoa crisis could lie in regenerative agriculture and incentivizing organic cocoa producers, as well as education.

Estelle, general director of an association of organic cocoa producers, organizes “Les Champs Ecole” to teach her people how to fight deforestation in times of climate change and how to regenerate the soil. “We grow organically, not only because we respect natural methods, but also because we respect the soil we live in. We want to leave things as we found them, in their natural habitat”

I have also met many other women who grow local crops to feed their families, who are often employed in the cocoa industry. When the harvest is good, they even sell cassava, yams and okra at the local market or as far away as Abidjan. They cultivate their land using ancestral techniques, respect the soil as in regenerative agriculture, use natural pesticides and use mulch to preserve the soil’s moisture.

Portrait of Mafoudia Soumah, Azaguié.

Mafoudia analyzes some samples of the soil, Abidjan University.

Mafoudia shows a piece of earth, Azaguié

Estelle Konan checks the quality of the cocoa beans.

Cocoa planters wives harvest Yam in Sokrogbo.

Meeting with Wives of cocoa planters and Estelle, Sokrogbo.

Tomatoes harvested by the women association AVEC, Sokrogbo.

Teki Ofoué Antoinette smile proud of the harvest, Sokrogbo.

Mira Mariani was born in Italy in 1983. During her secondary education she artistic training and then obtained a university degree in conservation and conservation and enhancement of cultural heritage at the University of Milan, specialising in art history. She soon returned to her first passion passion for photography. In 2007, with the birth of her first child, she became fascinated by unconventional childbirth and studied the history of childbirth. In 2012 she began training in photography of newborn babies and portraits of pregnant women. Mira has lived in Côte d'Ivoire since 2013 with her husband and their four children. Her artistic work is viscerally linked to her journey towards parenthood.

MIRA MARIANI

Instagram: @mirafrique

REBIRTH

By Romane Dakwa

Climate change is a pressing challenge facing humanity today.It is against this backdrop that “Renaissance”, a personal report, highlights the importance of the actions that some people are taking to reverse this trend and protect our planet from climate change for future generations.

To do this, they are adapting more sustainable lifestyles, such as favouring local and organic produce and recycling waste. For example, turning compost into organic fertiliser is beneficial for soil and plants. The resulting product, which is natural and sustainable, reduces the need to use chemicals that are harmful to soil and plants. This is why Sayouba Sawadogo, an agricultural engineer based in Abidjan, founded and managed Magic-éco groupe in 2020, the first branch of which was Magic-culture, whose role was to support, finance and monitor farmers’ projects.

He discovered a problem of soil impoverishment and degradation despite the constant use of chemical fertilisers during a supervisory mission. Production quantities were steadily falling. On surveying the land, he discovered that it was devoid of anything that would enable plants to produce normally. Sayouba decided to put a stop to this by finding a formula for transforming organic matter into fertiliser. So he launched Magic-compost, the second branch of the Magic-éco group, which will involve recovering organic matter such as cocoa peat, poultry droppings, coconut powder and dead grass through a carefully monitored process of transformation into organic fertiliser. Having obtained a positive result after several tests, he began marketing his product. In view of his commitment, he has won several prizes in Côte d’Ivoire and abroad. Bodji Toussaint, a resident of Ligrohouin village, 250 kilometres from Abidjan, is a trader and planter. After hearing about this product in 2023, he decided to come to town to buy the fertiliser and sell it to local planters.

Unfortunately, the drought has made it difficult for him to sell his stock to the villagers. The villagers think that chemical fertilisers are preferable to organic fertilisers, which are more effective on the land. But Gnaoré Christ, who used to work for a local company in Abidjan, finds himself back in the village after the death of his father in 2023. The eldest and only son in the family, he took over the running of the deceased’s plantation. Helped by his cousin Dalogo Armand in the field work, unlike the other planters, who were aware of the dangers of chemical fertiliser on the environment, they put their trust in organic fertiliser. They were happy to see their plantation keep its green leaves during the dry season, followed by a good harvest.

ROMANE DAKWA

Instagram: @romanedakwa

Romane Dakwa is a young photographer from Côte d'Ivoire, born around Dabou in 1998. He first became interested in photography through the work of his brother Raymond Dakoua, a photographer based in Brussels. For several years he lived in Bondoukou, in the Gountougo region of Côte d'Ivoire, where he discovered the savannah landscapes and market gardening techniques. In June 2023, he took part in the group exhibition "Polymères, Arts Plastiques" at the Musée des Cultures Adama Toungara (MuCAT), Abobo, Abidjan, where he exhibited a selection from his report "The Power of Plastic", about the pollution of urban landscapes.

When Hope Meets Nature

By Zahui Yvann

“When Hope Meets Nature” suggests a harmonious relationship between human aspirations and the natural world, where hope acts as a catalyst for environmental stewardship and collective action. Central to my work is the exploration and celebration of the innovative practices championed by INFPA (INSTITUT NATIONAL DE FORMATION PROFESSIONNELLE AGRICOLE) under the auspices of the Ministry of Agriculture.

The institution does above-ground production in greenhouses, cultivating crops within a controlled environment. Greenhouses provide a controlled climate, allowing for year-round cultivation and protection from adverse weather conditions. Not only in crops but how animal excrement plays a crucial role in enriching the soil through nutrient cycling. I delve into the good and bad practices such as the use of pesticides. Pesticide residues can contaminate food and water sources, leading to ingestion, further health risks, and death. A clear example from the Gôh region in Gagnoa (Kpapékou), where a family of four suffered food poisoning from pesticides.

Despite the perception of agriculture as outdated or unremarkable, it serves as a dynamic and innovative field with significant potential for growth and development. Through my immersion at INFPA, I had the opportunity to engage with students who are passionate about driving change and innovation within the industry. These students are eager to pursue projects and studies that can revolutionize agricultural practices, yet they often face challenges in securing adequate financing and support.

I talk about how regenerative agriculture, a transformative approach that remains underrepresented among practitioners in Côte d’Ivoire. Regenerative agriculture holds profound importance for the future, not only as a means of sustainable food production but also for its potential to address pressing environmental and social challenges.

Côte d’Ivoire faces environmental challenges like deforestation and soil degradation, threatening its ecosystems and biodiversity. This approach also helps mitigate climate change effects, ensuring the preservation of natural resources for future generations.

“Wings to fly” is a metaphorical expression often used to describe the concept of providing support or opportunities for growth and success. In the context of agriculture, this could refer to various strategies, technologies, or initiatives aimed at improving farming practices, increasing yields, enhancing sustainability, or empowering farmers.

Greenhouses provide a controlled climate, allowing for year-round cultivation and protection from adverse weather conditions. I delve into the good and bad practices such as the use of pesticides. Pesticide residues can contaminate food and water sources.

Before entering a hutch or a coop, the farmers engage in acts of cleansing, to avoid bacteria and infections from hurting the animals as they may be sensitive to them. The coop itself emerges as a sanctuary, its walls adorned with vibrant murals depicting scenes of renewal and growth. The transition into a space of collective nourishment and community.

The digestive system and vegetables merge seamlessly, evoking a sense of harmony, vitality, and interconnectedness between the body and the bounty of the earth. They intertwine with anatomical structures, blurring the lines between human anatomy and the natural world.

Addressing misinformation in regenerative agriculture requires promoting accurate information, fostering transparency and accountability within the farming community, and supporting scientific research and evidence-based practices. Educating stakeholders about the principles and benefits of regenerative agriculture can help dispel myths and ensure that efforts to transition towards more sustainable farming practices are based on sound knowledge and understanding.

Zahui Yvann (Cote d’Ivoire, 2001) is an art director and visual artist/photographer. His visual language is deeply rooted in Afrofuturism, through which he blends photography and constructed images to express his African identity and shed light on the societal issues that confront today’s generation.He studied Filmmaking and Multimedia Computer Graphics at Accra Film School (Ghana).

He worked at Voodoo communication Group as a Graphic Designer. Since 2022, he works as an art director at MW DDB.In 2020, He became a Catchlight Student and exhibited in the “Still I rise” exhibition of Aida Muluneh. He also worked on projects such as “Road to Glory - The Nobel Peace Prize 2020” and “Reframing Neglect - End Fund”.

Zahui Yvann’s work has been shown at the Institut Français du design for the Biennale internationale du Design Saint Étienne for Explore Outside The Box (France), MuCAT (Musée des Cultures Contemporaines Adama Tougara) (Ivory Coast) and Windsor gallery (Ivory Coast). In 2022 he became part of the 40 artists selected by Vogue Italia, for the Photo Vogue Festival in Milano (Italy).

zahui yvann

Instagram: @zahui_yvann

GOLIKRO II

By Olivier Kouhadiani

Through the figure of the protective divinity Goli, this series explores the symbolic and narrative power of the mask in Baoulé culture.

The photographs feature children from the village of Amanikro, acting out what are symbolic interpretations of the mask. Representing traditional guardians of social cohesion and order, the mask also symbolises strength and wisdom. Within cocoa-growing communities, the masks ensure sustainable farming practices, help combat child labour and promote harmony between ecosystems and cocoa cultivation. These functions have come to echo their contemporary role as “ecological brigadiers”.

Goli masks can represent a number of animals whilst performing a variety of roles. They report village events, accompany women during times of fertility and pregnancy, protect the village from all evils, settle conflicts between people from the same and from different villages, are present at funerals, chaperone the deceased into the afterlife and act as intermediaries between the physical and supernatural worlds.

The wearer’s physical appearance has been reinterpreted here, as has his role. Each photograph mimics either a creature, a moment of community surveillance or a beneficial action. The children, or rather the ‘Neo Goli’, interact with the village, a place which had nearly forgotten its existence and its importance after being relocated.

Appropriating ancestral symbolism, the children remind us that in addition to preserving the traditions, cohesion and strength of the village, present and future generations have a responsibility to protect the land and its resources.

Golikro II is the continuation by the author of Golikro, produced as part of the Advanced Visual Storytelling Programme supported by the Chocolonely Foundation in 2022-23.

OLIVIER KHOUADIANI

Instagram: @olivier_khouadiani

Olivier Khouadiani is a photographic artist based in Abidjan, Ivory Coast. At the crossroads of journalism, fine arts and street photography, his work explores the themes of globalization, identity and the place of African culture and traditions in the contemporary world. He is a co-founder of Photowalkers Anonymous, an initiative that cultivates a deeper sense of community, challenges perceptions of one's hometown, and brings people from all walks of life together through their shared interest in photography.

Indigénat

By Kra Kouassi

The story of plantation in Côte d’Ivoire, in (West) Africa

Arthur Verdier (1835 - 1898) was a native of La Rochelle who arrived aboard the Sainte-Anne at the French trading post of Grand-Bassam where, in 1864, with the help of Dutch capital, he set up as a trader. In 1881, six years before the signing of the French treaties that established the French presence in this part of the Gulf of Guinea, he set up a coffee plantation in Sanvi country, on the banks of the Any lagoon at Élima. The first plantation in Côte d’Ivoire. In 1893, when Côte d’Ivoire was officially proclaimed a French colony, a Jardin d’essai was created in Dabou. The successful addition of this group of territories to the French colonial domain required, among other tools, the management of nature and population perceived as hostile. In 1900, the Dabou’s Jardin d’essai became a Botanical garden and was transferred to Bingerville, where it is still located and retains the same name.

After a few trials at the Colonial Laboratory of the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, the former Jardin des Plantes, the Colonial Garden at Nogent-sur-Marne in France was created in 1900 to “study the characteristics of tropical products with a view to their use by French industry, and to propagate and disseminate the plant species that supply these products1”. A number of West Indian and American plants were introduced to Bingerville and Côte d’Ivoire from the Nogent Garden, or from other Botanical gardens in the French Empire, whether alive, dead or from seed. Maize, manioc, cocoa, rubber, and cashew nuts’ trees are all examples of so-called useful or economic Ivorian crops that originated in the West Indies and the Americas. Along with other plants, they have survived the era of Botanical gardens, and the scientific and aesthetic display of their mastery of nature. At the beginning of the 20th century, they became part of experimental stations. Away from urban areas, through a choice of varieties, larger-scale experiments, and the addition of fertilisers, species that were already cultivated had to be improved. Botanical research was totally dedicated to profitability.

Grand-Bassam, Dabou, and most certainly Sassandra, Grand-Lahou and Fresco, which I have not yet been able to research, were already home to “plant ruins2” before independence, the heritage of a Côte d’Ivoire that extended well beyond the coastline. These gardens were home to what can be described as intensive agriculture, the forerunner of the agriculture we have inherited. It seems to me that we cannot do without exploring the historical roots of this agriculture if we hope to regenerate it.

In the heights of the Andes and certain mountains of the West Indies, from the 17th century onwards, the cinchona tree was the object of fierce predation by Europeans who had come to this part of the world at the end of the 15th century. They established trade and cultivation of this plant throughout the world, as it was used to combat malaria, then an international scourge.

[[Quinquina luisant, Jean Théodore Descourtilz, Image tirée de la Biodiversity Heritage Library. Contribution du [Missouri Botanical Garden, Peter H. Raven Library ] www.biodiversitylibrary.org]

Acclimatising the pineapple in Europe required considerable effort. The first acclimatisation gardens were in Spain. They played a pioneering role in research into the practical conditions for adapting distant plants. They housed trials speculating on how to improve these plants for colonial expansion.

[[Yellow pineapple, Jean Théodore Descourtilz Image taken from the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Contributed by [Missouri Botanical Garden, Peter H. Raven Library ] www.biodiversitylibrary.org]

“The success of this country is based on agriculture”. Success defeated. Sick land and sick crops. What scarecrow remedy? What indigenousness?

[[Cultivated cocoa tree, Jean Théodore Descourtilz Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Contributed by the [Missouri Botanical Garden, Peter H. Raven Library ] www.biodiversitylibrary.org].]

Industrial crops were designed to enrich the metropolis. The raw materials extracted in Abengourou, Dabou, Bingerville and Gagnoa generated direct and related activities that can be seen in Bayonne, Bordeaux, La Rochelle, Rochefort and their hinterlands. What needs does Ivorian agriculture meet today? [[Greenhouses in the Colonial Garden: the Menier pavilion © CIRAD, 00001416 ]]

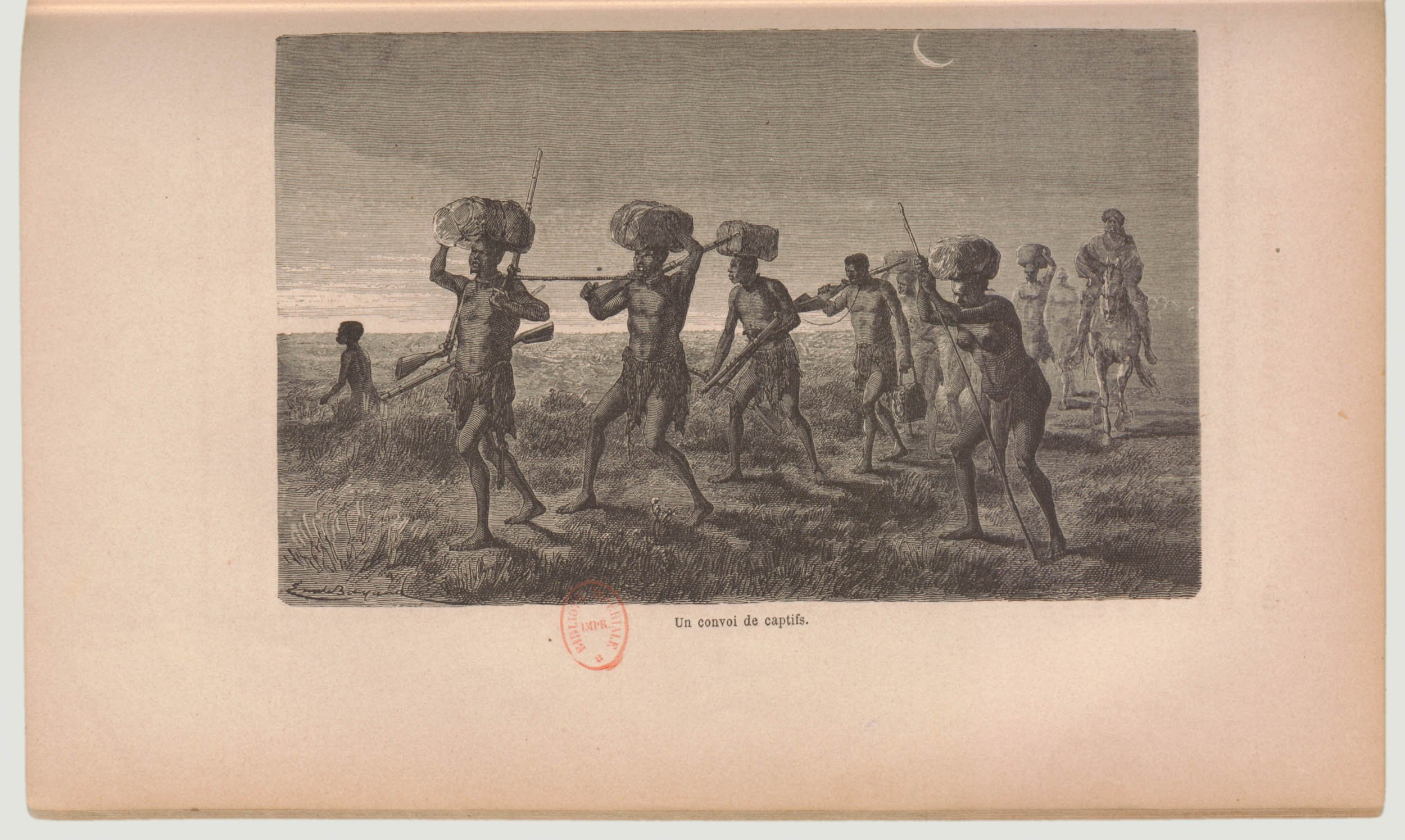

Before the land of colonisation was exploited, “India coin” or “ebony” was the African natural resource that was massively exploited in world trade. It was a commodity on a par with all ship cargoes from the 15th to the 19th century.

[A convoy of captives, Mage Eugène. Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France]

In the French empire at the turn of the 20th century, the need to exhibit winter gardens was giving way to the quest for greater profitability. Their tools and forms changed. What “indigenous” and innovative tools can we use to transform our culture of colonisation? How can we repair the silent roots that link us to the earth?

[[Orangerie, vue prise du petit labyrinthe], [circa 1885]. Pierre Petit (1831 - 1909), Photograph, black and white. Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, IC 654 ]

Connection between slave trade and agriculture in Côte d’Ivoire, in (West) Africa

The history of African and Ivorian agriculture to which I have had access is based mainly on European written sources. Some have drawn on African oral sources on both sides of the Atlantic, in particular for the so-called vernacular names of plants, and by invoking the myths of certain peoples.

From the middle of the 15th century, the Portuguese established plantations where Black African slaves worked. Sugar cane, which would later be introduced to the “New World”, was grown. Several islands on the African continent were laboratories for what would be established on a larger scale in the West Indies and America. In the second half of the 16th century, the transatlantic slave trade expanded. Networks of gardens were established along the routes of the slave-trading explorers. Port gardens in France were necessary for the acclimatisation of African and American plants before they were transferred to the Jardin du Roi, later Jardin des Plantes in Paris. The fort gardens on the West African coast provided sustenance for the extremely large numbers of people who were drawn into this new trade, whether willingly or by force. They were also among the first places where West Indian and American plants were introduced to Africa. At the time of the abolitions, freed Africans returned from the Americas and contributed to the introduction of more West Indian and American plants and their spread in Africa. At the end of the 19th century, the French presence on the “ivory coast” dared to extend beyond the coastline. On the Gulf of Guinea, some gardens adjoining the forts built at the end of slave trade’s routes, including the one at Dabou, were transformed into “Jardins d’essai” and then into “Botanical gardens”. These were instruments of the Europeans’ desire to exploit Africa’s natural resources without intermediaries, systematically and on a massive scale.

At the beginning of the 20th century, it was necessary to improve the species already cultivated by selecting varieties, experimenting on a larger scale and adding fertilisers. Botanical stations in open fields away from urban areas took over from urban botanical gardens.

[Contributions à l’étude du caféier en Côte d’Ivoire, Centre de recherches agronomiques (Bingerville, Côte d’Ivoire) Source: CIRAD].

What is peaceful colonisation? Haven’t we been infected by defeat? Where can we find our monument, our glory in all the wealth generated by our sweat, our soil? What is a “exotic pathology”? How do we know when we are being poisoned? How do we feel inside?

[Monument aux pionniers de la Côte d’Ivoire_La Rochelle_Carte postale_Ramuntcho (Raymond Bergevin), 1930s. Archives municipales de La Rochelle, 1OFI 2124]

Kra was trained in political sociology and in anthropology. She wrote creative pieces for online publications. She also produced and hosted a radio show where she provided her own version of historical fiction that blended micro history and music. She was a researcher and a teacher before deciding to fully dedicate herself to documentary projects. She tries to reach a more intimate form of knowledge through creation.

KRA KOUASSI

The NOOR Foundation is a non-profit organization fuelled by an unwavering passion to inspire action on the most pressing challenges of our era through the power of visual storytelling.

Education is the bedrock of our endeavours, we are called to commit to the discovery and support of emerging visual storytelling talent from a plurality of backgrounds all across the world. We facilitate the development and production of the stories that matter, learning and co-creating every step of the way. We actively promote the creation and dissemination of impactful narratives, crafting a diversified web that strives to ignite a transformative shift in how we portray and understand our world.

Our mission is to create thought-provoking, multidisciplinary visual projects that make a meaningful impact on the world and inspire purpose-driven action. We aim to cultivate an environment where a vibrant tapestry of varied viewpoints can flourish, paving the way for a truly interconnected community with narrative threads spun all over the globe.

Supported by The Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands