I Exist: European Stories of Islamophobia

The narratives included in I Exist seek to perform a challenging task: amplify the voice of those often marginalised in the contemporary discussion of Islam and its role in Europe. Bringing together the work of five photographers, Nina Berman, Tanya Habjouqa, Olga Kravets, Bénédicte Kurzen, and Sebastián Liste, I Exist shares the personal stories of Muslims in Spain, France, Belgium and Italy, hoping to live as citizens but othered in a hyper-visible and critical reality. Exploring the diversity of the European Muslim experience as well as the diversities of European Islamophobia, these stories provide an opportunity to counter the narrow, brittle, and false vision of a Europe besieged by ravening Islamic fanatics bent on destruction.

How the increasing religious diversity of Europe will manifest itself in the years to come is a key topic in the works included in I Exist. Some responses have been constructive, as documented by Nina Berman in the Belgian town of Mechelen, where social policies are fostering inclusivity and combatting both stigma and extremism. In other cases, matters have been more contentious, with far-right parties exploiting ambient suspicions and prejudices.

tHE PROJECT WAS EXHIBITED at the Melkweg Expo BETWEEN September 4th to October 10th, 2020.

““As a Jordanian-American raised in both countries with secularism and cultural Islam, I never struggled with my place as an atheist in the family. It was a fluid experience. My devout grandmother was the first woman in Amman to get her driver’s license, a feminist; the only one of her sisters who did not wear hijab. It never mattered in our house, it was always a personal choice. The Western preoccupation with hijab has always irritated me.”

— Tanya Habjouqa, NOOR Author ”

Tanya Habjouqa

Diary of Inquietude: Testimonies of French Muslim Women

“Whatever Muslims wear – and despite this being by choice – Muslim women in France find themselves in the middle of a secularism debate they have no voice in.” Widad Ketfi, French journalist.

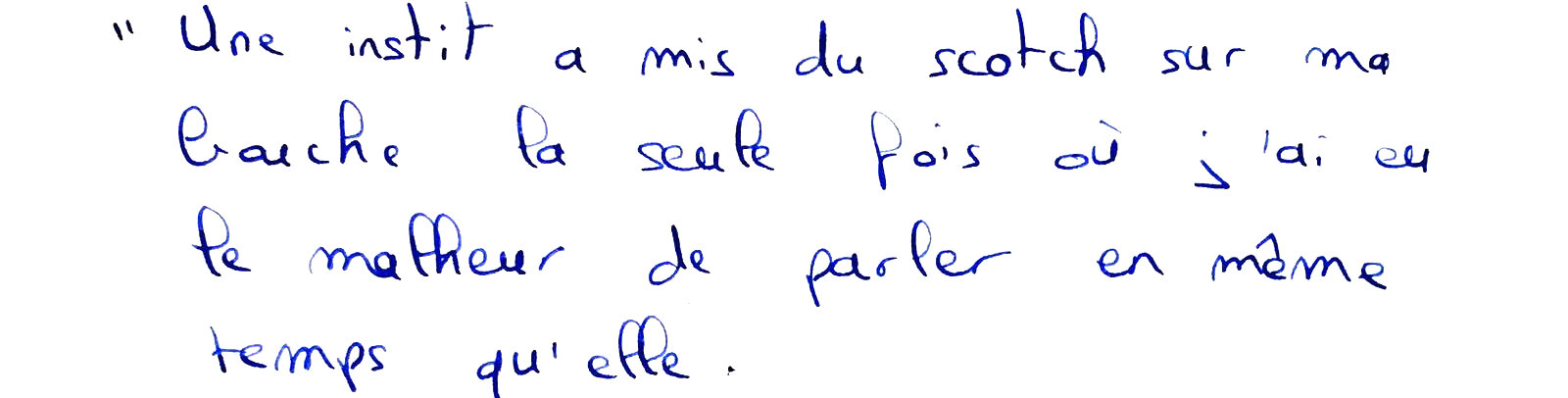

Muslim women can have a modern interpretation of Islam and their own vision for feminism, so why is the policing of women’s bodies continuously institutionalized by the French state? This is the question that guided my multidisciplinary audio-visual investigation into the lives of French Muslim women and girls across France. A collection of audio testi- monies will be utilized to create ethnographic soundscapes for the exhibit, and as a source of material for the print edition of our project. The audio tracks are a record of oral history. Video and still portraits were taken in collaboration with participants, mixing a recreation of memories, absurdist commentary, and traditional portraiture.

“After graduating from university in Economics, I decided to reinvent myself as a baker. I went to take the exam, which took place in a public high school. A representative of the high school asked me to remove my scarf. I refused. He said that my scarf was forbidden, but I explained to him that since I wasn’t a student nor working in the school, the rule did not apply to me. He insisted. I felt trapped. It was rude to go because there were demonstrators who came just for me to the test. I tried to explain that it didn’t make any sense and that, to me, it was like asking to take off my trousers. He didn’t get it, or didn’t want to, I don’t know. It was very hard because I knew I had the right to keep it.

Then, I hid in a corner of the room, I tied my scarf around my head and he asked me if I wanted to put on a plastic cap to be more comfortable. I answered that the most comfortable to me would be to keep my scarf. Then he left. The representatives of the company were really embarrassed because I was crying out of humiliation. I wrote to the local authority of Education, and a few weeks later I received a letter from the high school with apologies.”

Rym, baker, 36, Paris.

Sebastian Liste

In 2014, 49 islamophobic attacks were recorded in Spain. By 2016, that number was 573. According to the Office of the Attorney General, the numbers continue to increase annually.

Though new reports show that 70% of islamophobic attacks now happen online, confrontations in mosques and on streets across the country remain common.

We examine the impact of this hostility by focusing on Ceuta— a city along Europe’s southern border, and one of only two on the African continent, where more than half of the population identifies as Muslim.

Even Ceuta, with its long history of successful cooperation between religious communities, has recently experienced increases in racism and xenophobia. This work looks at four young Muslim women born and raised in the city, who provide insight into their daily lives.

This project rethinks the way we create stereotypes

and myths by deconstructing the four major myths facing Muslims in Spain:

Myth 1:

“The hijab goes against women and shows a lack of integration in Western society”

Spain, Ceuta, October 2019 View of the city of Ceuta, Spain. Ceuta, is Europe´s Southern border, with Melilla, there are the only two European cities located in the African continent. Due its vast diversity of cultural influences among the Mediterranean Sea commerce routes and its link with the neighborhood country Morocco, more than half of its population identify themselves as Muslims. This scenario have made possible a pong history of successful cooperation among different religion communities with the Islam, that can lead the path of coexistence for the raise of Islamophobia in Europe. But even here the city of Ceuta, have not been immune to this increase of racism and xenophobia and extreme right-wing political parties are rising with their violent and hated speech against the Islam. Sebastian Liste / NOOR

Samra Amar Ahmed (26), works as a make-up artist and is mother of a 2-year-old child. She has experienced several incidents in her life due her religion. In the University, she faced awful situa- tions when her classmates didn’t want to sit near her or include her in any group exercise.

Naryis Abdelkader Bunuar (24) grew up in a liberal family where creative and service to the commu- nity were the core values. Her mother runs an art community center at home and her father has been working for many years with Unaccompanied Foreign Minors crossing Ceuta ́s border.

She was raised in a Muslim family where respect, tolerance, love and help to others were crucial to become a social worker and study nursing.

She considers herself as someone with a lot of freedom, even though she knows there are limits to a Muslim living in Spain...

Jadill Abdelrraman Lachkar (23) is studying Law at the University of Ceuta, while preparing for com- petitive exams to work in the judicial system.

For her, Ceuta is a unique place with a long history of coexistence among four different religions, Muslim, Christian, Jewish and Hindu. The restof Spain is different, in the Peninsula the people don’t associate the hijab (veil) with Spanish born people, and she identifies herself as Spanish, inde- pendently of her religion or beliefs.

Olga Kravets

Olga Kravets Islam in Italy: An Inventory

On a cloudy October morning, I met Yassine Baradai, of the National Secretary of the Italian Union of Islamic Communities, in the town of Casalpusterlengo in Lombardia, northern Italy. Together we set out to the local Islamic Cultural Association.

We enter a bright red, two-story building that with each step transforms more into a spacious, beautifully renovated prayer hall. The building has been a plank in the eye of local members of Lega Norte, Italy’s most islamophobic party, since its 2016 establishment.

“We are famous as a region of a thousand church towers. We don’t want to become a region of a thousand minarets. So we have used every trick

in the urban planning books to stop the spread of mosques,” Massimiliano Romeo, a Lega politician, said in a 2017 BBC interview

Italy, Naples, 20 October 2019 Fatiha Melzi (center), a teacher of Arabic at the Napoli Islamic Community center, during her class for young children. “I had street accidents, when people noticed my hijab and insulted me. What happens in passing, you know…Was it Islamophobia? I don’t know. I preferred to just shrug it off”.

Renata, who goes also by her Muslim name Amira after she converted, is photographed after her Arabic language class at the Napoli Islamic Community center. Renata is a former Italian army pilot. She discovered Islam while on a mission in Afghanistan back in 2007. She now flies civilian planes for a prominent international airline.“In Afghanistan, I used to bring food to poor people outside the army camp. I got close to Islam because I saw poverty and people with a big heart. Even in the midst of war, they still prayed. I feel that we, Muslims, are still discriminated a bit. For instance, I am discriminated at my job: you can’t pray, the hijab is forbidden, some people were banned from the company altogether. It’s because people need to be identified, especially after September 11. If I could pray during autopilot, I would do it, but I prefer to express myself here [among fellow Muslims], not outside”.

Italy, Castegnato, 23 October 2019. Raisa Labaran, a Muslim activist, photographed at home in the town of Castegnato outside of Brescia, in Northen Italy. Raisa works as a cultural mediator, writing her thesis from nursing school, gives classes to kids, as is a founder of MaiPiù (“Never Again”), an initiative against Islamophobia in Italy. “At 13, during a school trip, was when I realised I’m not the same [as the other students’], I realised I would always have to struggle in my life. My mom is from Ghana, my dad from Nigeria. Here in Italy, if your parents are not Italian but you feel Italian, you’re lost. My mom used to say: “You need to get good grades because you’re already a child of immigrants, you need to show your value even more”.

Benedicte Kurzen

Bénédicte Kurzen— State of Emergency, France

In “State of Emergency” Bénédicte Kurzen addresses the institutionalized logic behind islamophobia and its genealogy. After the 2015 Bataclan massacre by Islamic State shooters in Paris, the French government declared a state of emergency for two years. In 2016, by the time the state of emergency was lifted, only 23 of the court cases opened amid 4,457 house raids could be linked to terrorist activity. In effect, on October 3, 2017, what began as temporary measures became a permanent state of emergency, reinforcing the long-standing institutional persecution of a marginalized minority. In this project, Kurzen attempts to understand how a stereotype is built and sustained through her unique photographic approach. The bleaching flash hides faces, giving shape to the construction of the stereotype at the root of Islamophobia and illustrates how the over-exposure of the Muslim population, in a negative light, creates a toxic blur obscuring diversity.

Text written by French sociologist and political scientist Vincent Geisser:

En avril 1955, en pleine guerre d’Algérie, le gouvernement français fait voter pour la première fois de son histoire une loi instaurant l’état d’urgence sur son territoire dans le but de réprimer les nationalistes algériens qui luttent pour leur indépendance ; en novembre 2005 confrontées aux émeutes urbaines et aux mouvements de protestation dans les banlieues, les autorités décident de ressusciter une législation coloniale afin de placer sous surveillance les quartiers populaires ; dix ans plus tard, en novembre 2015, face à une vague d’attentats qui endeuillent la nation, les pouvoirs publics renouent avec l’état d’urgence afin de démanteler les réseaux jihadistes et de prévenir de nouvelles attaques terroristes sur son territoire.

En apparence, ces trois moments forts de « restauration » de l’état d’urgence dans l’histoire récente de la société française n’ont pas grand-chose à voir entre eux et il serait peu pertinent d’établir un continuum à la fois historique et sécuritaire. Mais à y regarder de plus près, les représenta- tions et les motivations qui président à l’adoption de telles mesures exceptionnelles semblent participer d’un imagi- naire commun, visant à assigner, contrôler et surveiller des populations dont l’altérité culturelle et religieuse est perçue comme conflictuelle et problématique…

France, Lyon, January 2020 The Shahada symbolises the first pillar of islam. It is confirmation of the muslim faith.

“J’ai réalisé ce jour la, q’ils te font passer pour ce qu’ils veulent. Ca passe créme. L’autre ma mis le dans le coup. Le gars a sauté se le lit avec une arme de guerre. C’est moi qui leur disait de se calmer.

France, Marseilles, January 2020 Patricia, 53 years old, converted to Islam when she parried Abdelkader and immediately wore the veil. She is originally Italian: "I wanted to be a nun when I was a child, but I also wanted to have children. With Islam, I can wear the veil, have a spiritual life like a nun and brought up 4 children. It is perfect." The house raid was so brutal that it triggered diabetes.

France, Lyon, January 2020 Abdelaziz is a militant from Lyon, originally from Tunisia. He defended during the state of emergency the Msakni family whose children had been taken away from because of "radical practice of Islam" according to the judge. "Abdelaziz Chaambi est un militant lyonnais d’origine tunisienne. Il est issu d’une famille très fortement engagée contre la présence coloniale française en Tunisie. Il a été un acteur important de la construction de l’islam de France hors région parisienne au cours des années 1980. En effet, il fut, entre autres, l’une des chevilles ouvrières de l’Union des Jeunes Musulmans de France qu’il a cofondée à Lyon en 1987. Très tôt sensible à la cause des plus démunis, de la condition coloniale et postcoloniale, il a milité dès son plus jeune âge dans différentes structures associatives ou au sein de mouvements politiques à l’instar de Lutte Ouvrière. Dans l’entretien accordé à Confluences Méditerranée, Abdelaziz Chaambi revient, sans ambages, sur les grandes étapes de ses engagements successifs et multiples dans la cité, sur la façon dont il articule foi musulmane et militantisme, sa lutte sans relâche contre les effets du capitalisme néo-libéral, le regard qu’il porte sur la situation de l’islam de France, le conspirationnisme dans les milieux musulmans, etc., notamment dans le contexte post-attentats de 2015 qu’il a vécu avec beaucoup de tristesse et de sidération." - Haouès Seniguer Bénédicte Kurzen / NOOR

SEE MORE FROM THIS STORY